Picture books? Really?

Recently I read a heart-warming article in the Nerdy Book Club blog by a man who loved picture books when he was a child. As a boy, he had no interest in chapter or age-appropriate books; he just wanted to read what he wanted to read. Specifically, he wanted to enjoy the illustrations and photos in picture books, which some people labeled as “baby books” for him. What a shame!

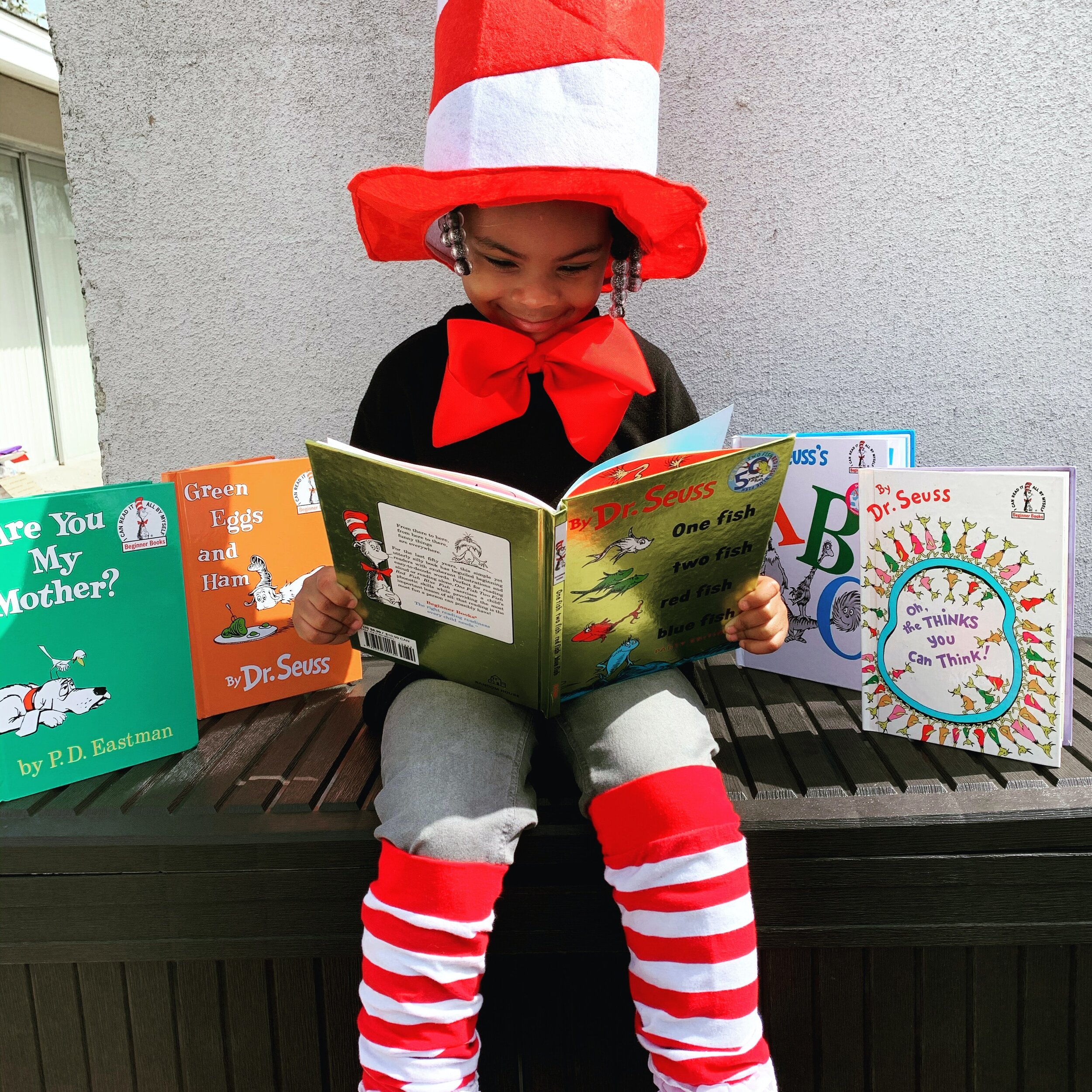

The aspects of literacy provided by picture books are their vivid images, delightful illustrations, fascinating diagrams and rich art. By being multi-modal, picture books invite enjoyment by everyone, children through adults, remedial and gifted readers, and people from a broad cultural range. Graphics spur fabulous conversation in which everyone can participate.

"Ooo! What's that behind the tree?"

"What could that mean?"

"What else did I miss at first glance?"

Each of us, regardless of our sophistication with the printed word, can enjoy visual beauty and design excellence. After all, we've engaged in visual meaning making from birth. Discerning meaning from printed words is a new game for most of us when we enter school, or when we first ask, "What's all this?," while pointing at letters found on the same page as an image. Soon thereafter we learn that it is words most folks care about; images become secondary.

The printed word, of course, becomes the major focus of many teacher-led experiences had by primary school students. However, if we wish to honor the unique contribution that varying visual media make to our learning lives, we need to add the print-focused meaning atop the foundation derived from illustrations and pictures.

Lessons that focus on discussing the words and images in picture books tend to support reading growth. These types of discussions also legitimize artwork as an enjoyable and informative avenue to rich vicarious book experiences.

The old saying about a picture being worth a thousand words doesn't mean that pictures are strictly meant to support words. It means that pictures often communicate more than words alone could ever say.

Too often, teachers and parents tend to be print-centric in their interactions with children around books. Fortunately, the author of the essay mentioned above had a parent who was not swayed by pressures from school and community to focus only on age-appropriate print aspects of books. Thus, he was the recipient of picture book gifts well into the upper grades.

And by the way, he grew up to become an author and illustrator of picture books. Picture that!